An avid reader as a child, at some point I remember being intrigued by a rather simple discovery: that most of the really interesting people in life came from difficult circumstances. I don’t remember any notable personalities, artists, writers, etc., emerging from the antiseptic world of suburban America (or any nicely developed stretch of society).

Suffering, it turns out, is the thing that churns up the sediment of the soul, leaves us uneasy, forces us to consider life through different filters. We hate suffering when we’re in the midst of it, but if we’re fortunate we also thank it when the dust has settled, when we’ve grown or learned something or evolved.

So you can imagine how happy I was to read another of Brain Picking’s marvelous essays, this time on Friedrich Nietzche’s belief that nothing meaningful comes of a life free of suffering. A fulfilling life, said Nietzche, is achieved “not by avoiding pain, but by recognizing its role as a natural, inevitable step on the way to reaching anything good.”

The thing is, to one degree of another all of us know this. The best meal is one consumed when we are ravenously hungry; a fire is never quite so welcomed as when we are shivering from the cold; the thrill of a new love always feels that much keener when it interrupts a long stretch of loneliness.

But suffering alone isn’t enough. We need to be conscious of it, recognize it for what it is. Failure to do so means the suffering will come and go without meaning or purpose. Like so many, an awful lot of my life was characterized by suffering. But also like so many others, I spent the majority of that time simply trying to get out of it. The suffering was something to be avoided or transcended or ignored – certainly not embraced or at least studied.

It was not until the Mother of All Existential Crashes in early 2006 that it at last occurred to me that god, life, whatever, was trying to tell me something. That a lifetime of gradually escalating suffering was an offering rather than some form of punishment. And I’m oh-so grateful that something – a grace, if you will – at last saw that suffering for what it was and rather than working to overcome it instead focused on understanding it. That, of course, remains a work in progress.

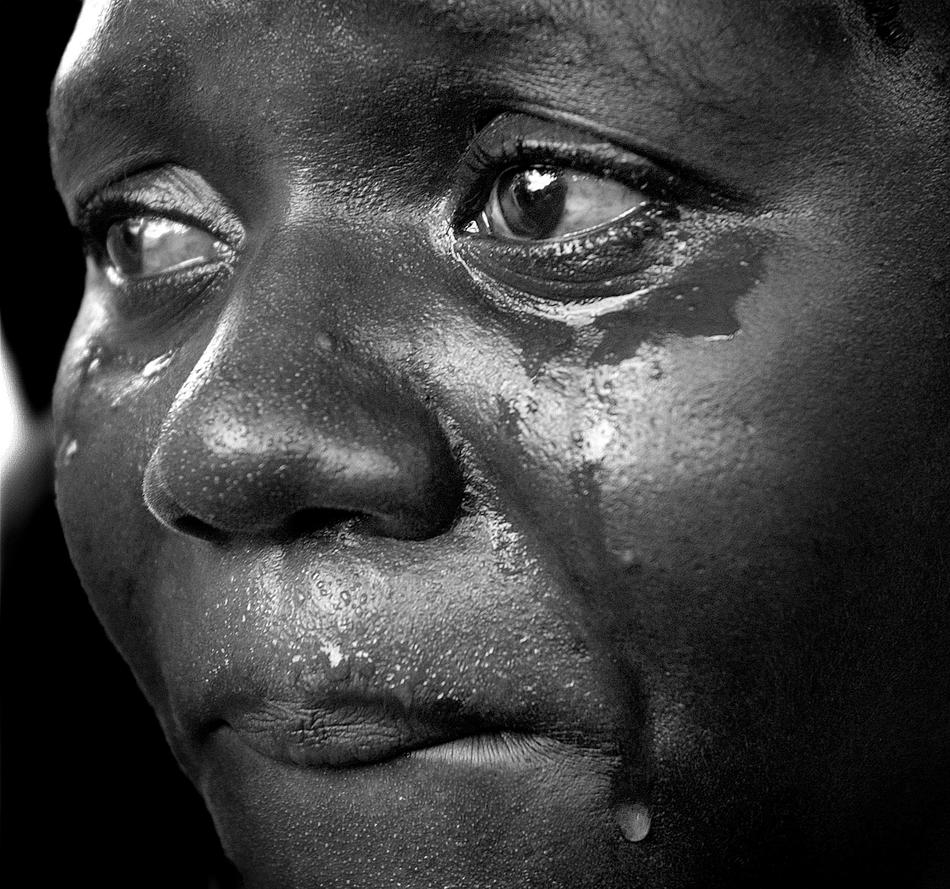

So here’s the question: Once we come to see suffering as a gift, why do we nevertheless work so hard to keep those we love from experiencing it? Why, as parents, do we strive to shield our children from any form of suffering, to remove all of life’s hard edges, to grease the skids so that they might “enjoy a lifetime of material comfort and success”? Why, when a loved one weeps from pain, do we instinctively wrap our arms around them, whisper that it will be ok, or wish that we might take away their pain?

It is telling that, when asked what he most wanted for those he loved, Nietzche responded: “Suffering, desolation, sickness, ill-treatment, indignities – I wish that they should not remain unfamiliar with profound self-contempt, the torture of mistrust, the wretchedness of the vanquished.” He added: “I have no pity for them, because I wish them the only thing that can prove today whether one is worth anything or not – that one endures.”

The brain – not just human, every species’ brain – is said to have evolved to enable increasingly sophisticated creatures to safely navigate a world that otherwise might eat, burn, drown, or crush its them. The brain developed sophisticated neural pathways and motor connections to warn: “Cliff! Lava! Alligator!” It learned to separate pleasure from pain, to seek more of the former and to avoid the latter.

But the thing is, the brain never ceases in such pursuits. Like a mindless (pun intended) automaton, the brain keeps seeking comfort and eschewing pain regardless of how well-appointed the home, how stocked the pantry, how healthy the body. We become ‘helicopter parents’ endlessly obsessing about the welfare of our children; we become hypochondriacs racing to the doctor for every ailment real or imagined; we grow fat and indolent while our children become dull-eyed and complacent.

Helen Keller, who knew something of suffering, noted: “Character cannot be developed in ease and quiet. Only through experience of trial and suffering can the soul be strengthened, ambition inspired, and success achieved.” Interesting, isn’t it, that she led with a strengthening of the soul? To Keller and her ilk, ‘ambition’ and ‘success’ were not to be measured in the figures of a bank statement or the comfort of a home – they were to be measured in understanding the very nature of existence itself, why we are here, who or what we are.

Maybe, in the end, the ultimate expression of love for another is, as Nietzche suggested, to hope for our loved ones a modicum of suffering; to let them thrash about, to struggle for air, to dive deep within and not merely cry out, “Why me?” but to go further and ask, “What am I?”